What are some names for Still’s in Children?

- Still’s is primarily a disease of children under age 16 yrs, with most having an onset age between 4-8 years.

- When diagnosed in childhood, it is called systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) or “sJIA” or “soJIA” or “Still’s” disease during childhood.

- JIA used to be called JA (juvenile arthritis), JRA (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis) or JCA (juvenile chronic arthritis). There are many “Types” of JIA – Stills or the systemic type makes up to 20% of children with JIA.

Still’s disease in the child and adult – are they the same disease?

- Yes. Children with Still’s disease (sJIA) and adults (AOSD) share the same clinical features (spiking fevers, transient rashes, polyarthritis, pleuritis, hepatosplenomegaly and high inflammatory markers on test), same response to specific therapies and share the same genetic associations. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the same therapy for sJIA and AOSD.

- The main differences are the onset age, and a prodromal sore throat (at the disease onset) is seen in 70% of adults but only a minority of children (< 15%).

How rare is Still’s disease?

- Still’s disease is exceedingly rare. Only 1.6-40 cases per one million persons (in the population) per year.

What is the Cause?

- The cause is unknown. Still’s disease is not genetic and tends to be acquired during childhood or young adulthood. It is postulated that an environmental or infectious trigger, in a susceptible person, activates and perpetuates inflammation. The key mediators of inflammation are interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 and IL-18.

Are their risk factors for developing Still’s disease?

- None are known or agreed upon by experts. One study from 1996, showed there was an increased association between Still’s onset and “stressful life events” in the preceding year (Odds ratio – 2.56).

What is a Still’s Fever?

- Still’s disease fevers are high and must be over 102°F. Fevers as high as 104-105°F are common. These typically “quotidian” meaning they recur at the same time each day (or night), usually late night (11 PM–2 AM) or late afternoon (3–6 PM). Fevers at 6-8AM are not typical of Still’s disease.

What does a typical Still’s rash look like?

- The rash of Stills disease is often called the JRA or rheumatoid rash. It is one of the three classic (or “triad”) features of Still’s disease: including 1) Still’s rash; 2) Quotidian fevers greater than 102oF (or 39oC) and 3) Polyarthritis. The Still’s or JRA rash is Evanescent or intermittent (comes and goes day to day), “salmon-pink” in color, arises during fevers, and will appear on the trunk, arms, and legs – never on the face, palms, or soles of the feet.

How often does Arthritis occur in Still’s disease?

- Joint “pain” (arthralgia) is not the same as “arthritis” – arthritis implies inflammatory swelling of the joint. Joint swelling in several joints is seen in > 80% of SJIA patients. Typically there is swelling of 4 or more joints (polyarthritis), affecting small joints (fingers, toes, wrists) or large joints (ankles, knees, shoulders, hips).

- Chronic polyarthritis or persistence of arthritis in children with Stills disease may occur 20-33% of cases and may lead to damage, disability or a pattern of arthritis that resembles “rheumatoid arthritis” (but tests for RA should be negative).

- treatments for the arthritis of sJIA is similar to that used in adult rheumatoid arthritis but is quite different that treatment used to control the systemic symptoms (fever, rash) of sJIA.

Do I have Systemic or Articular (arthritis) Still’s disease?

- This is an important distinction as Stills may start out Systemic but evolve into Articular disease.

- “Systemic” Still’s disease is often seen at the disease onset and is characterized by spiking daily fevers, intermittent rashes, sore throat weight loss, enlargement of lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), liver (hepatomegaly), spleen (splenomegaly), or inflammation of the lining layer of the lung (pleuritis) or heart (pericarditis).

- Articular disease implies the dominance of joint pain, swelling and disability.

- Patients may have active Systemic and Articular disease simultaneously – often during disease onset.

What tests are used to diagnose Still’s disease?

- There is no “diagnostic” laboratory test, procedure, or biopsy. The diagnosis is based on a constellation of clinical and lab findings suggesting extreme inflammation. Typical laboratory (blood test) findings include: Extremely high white blood cell counts (WBC) and ESR (“sed rate” and CRP (all indicating inflammation). Half of patients will have remarkably high ferritin (iron) levels. Still’s patient will have negative tests for lupus (ANA negative) and rheumatoid arthritis (RF or CCP negative).

How should Still’s disease be treated?

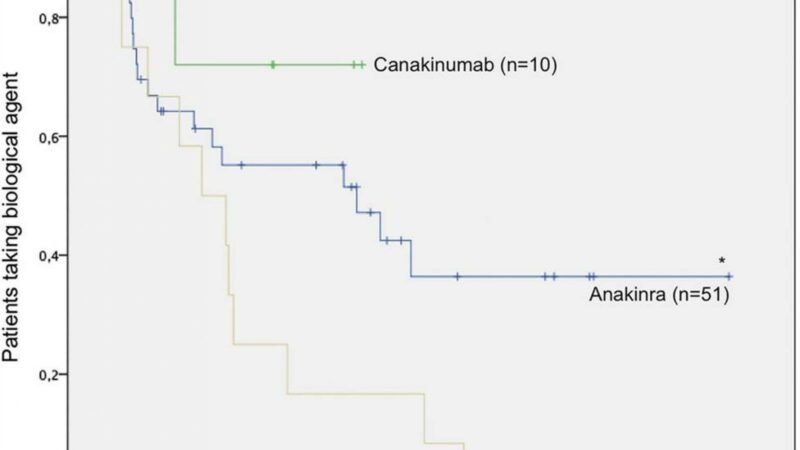

- Effective control inflammation (i.e., fever) often requires corticosteroids or “steroids” (like prednisone) at the outset. Doctors will often start inflammation suppressants as pills (methotrexate) or biologic injections (interleukin-1 inhibitors [canakinumab, anakinra], IL-6 inhibitors [tocilizumab, sarilumab]).

- These drugs are generally NOT effective in controlling Still’s inflammation (i.e., fever): colchicine, hydroxychloroquine, abatacept, rituximab, or TNF inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab or golimumab). Many of these may be used to treat the arthritis 0but will not help inflammatory features such as fever, rash, pleuritis, weight loss, etc.

- There is no diet to control the inflammation of Still’s disease.

Who should treat Still’s disease?

- Pediatric or adult rheumatologists or infectious disease doctors may diagnose and treat patients with Still’s disease.

What is the prognosis of Still’s disease?

- Patients generally of 8 months to 8 years of disease activity. While Still’s disease can cause problems or disability is seldom leads to death. Death related to Still’s disease is usually related to complications of chronic steroid use or the development of the macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

- Patients developing chronic inflammatory arthritis may have long-term, or chronic disability problems and will require ongoing care by a rheumatologist.

Author: John Swope

Related Content

-

November 26, 2019

A disease you’ve never heard of is becoming increasingly common and carries a…

-

August 8, 2019

A single-center cohort analysis shows that lung disease (LD) is increasingly seen in…

-

May 5, 2015

A retrospective review of 77 SoJIA patients revealed that 50-70% achieved inactive disease or remission…

-

May 14, 2022

Emapalumab Treatment in Macrophage Activation Syndrome: Dr. Fabrizio De Benedetti https://youtu.be/yHBRXphEhe0 Macrophage…

-

November 9, 2021

-

May 14, 2022

Dr. Olga Petryna - Canakinumab in Adults and Pediatric Still's Disease https://youtu.be/izWYPBbQyKk …